Effective Trial Design: Clinical Trials in Small Patient Populations

Continued progress in biomedical science makes it possible to deliver highly effective, targeted therapies for diseases that have smaller patient populations or small subset of patients in a larger indication, including certain types of cancer or multiple sclerosis, rare diseases, and pediatric indications.

The significant benefits of these targeted therapies make continued development crucial, while the small population of affected patients can present some challenges in the drug development lifecycle, including:

- Low number of patients available for clinical trials

- Longer recruitment times for clinical trials

- Increased number of clinical sites participating in a single trial. This may be required to include enough patients in the trial, and increases both complexity and cost of the trial

- Large heterogeneity in patient populations

To minimize these challenges, and the number of patients required for a trial, several statistical methods and designs can be used where:

- Each patient serves as their own control, e.g., Cross-over designs and N-of-1 trials

- The control group is not concurrently recruited but taken from external historical data, e.g., data registry

- Changes are allowed in the protocol of an ongoing trial, e.g., sequential designs or adaptive designs

For any study, choosing the most suitable design to achieve the maximum statistical benefit and optimize trial implementation should be given careful consideration. The two most important questions to ask are:

- Is the disease chronic or progressive?

- Is there any historical data available?

Specifically, the nature of the disease under investigation will help you determine whether each patient can serve as

their own control:

- Chronic disease: Remains relatively stable over a certain time period and will return to a comparable state once treatment is stopped, e.g., diabetes mellitus or asthma

- Progressive disease: Will not return to a comparable situation once treatment is stopped, e.g., cancer or appendicitis with resection

The characteristics of the treatment (e.g., half-life) and the primary endpoint (e.g. short or long term, variability) will also drive the choice of a design.

In this article, we will explore the pros and cons of clinical trial designs that can be effectively used to overcome the challenges presented by small patient populations with chronic and progressive diseases.

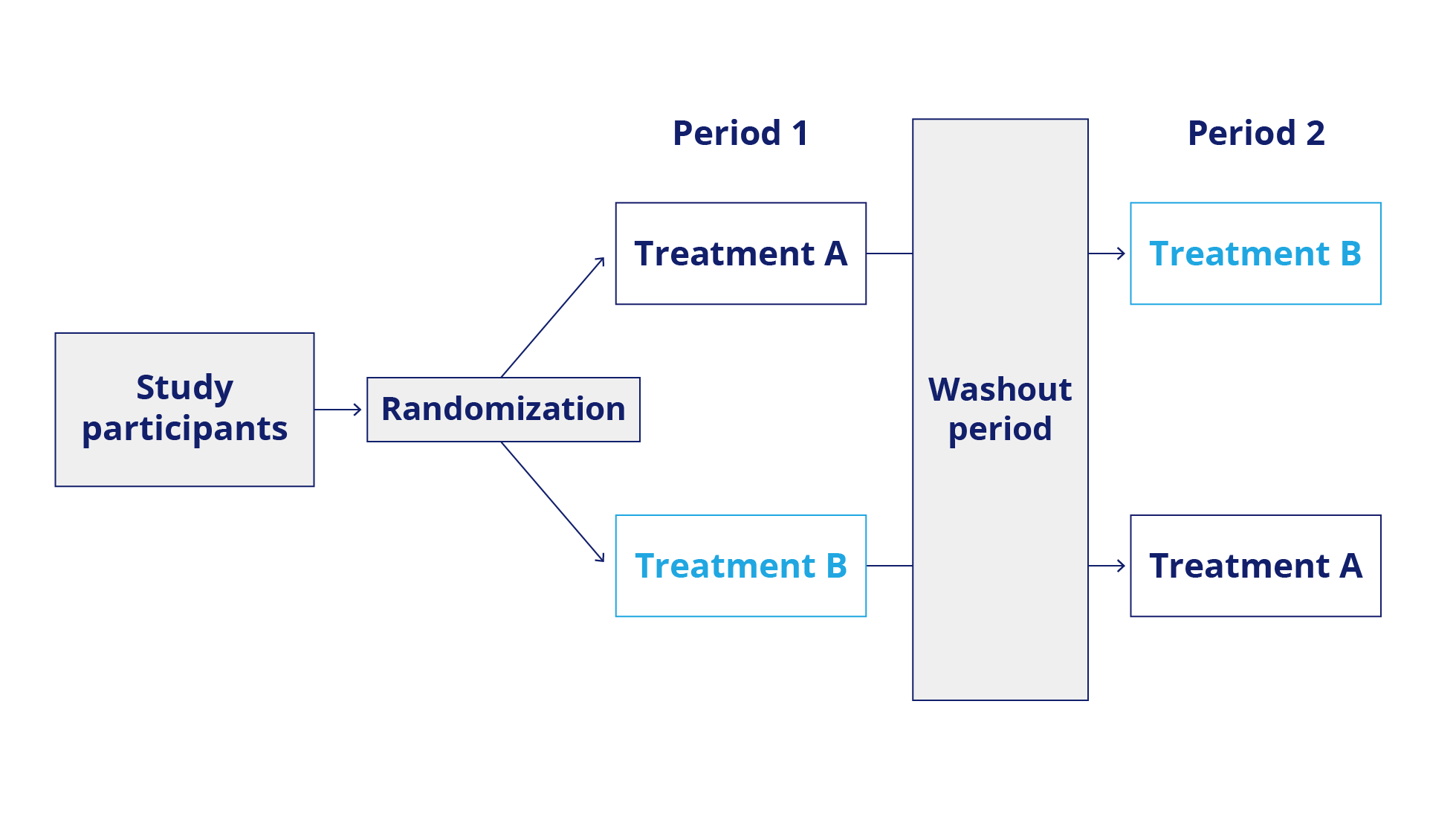

Cross-over Design: Chronic Disease

In a cross-over design, each patient serves as their own control and is treated in a pre-specified sequence on two different occasions with the compound under investigation and the comparator. This minimizes the sample size and addresses heterogeneity. Possible carry-over effects, i.e., that treatment in Period 1 still impacts Period 2, may complicate the analysis.

N-of-1 trials: Chronic Disease

Each patient serves as their own control in this design. The sequence of treatments is usually randomly assigned, and more than one judgment of effect per patient is possible. This design is most effective for endpoints that can be measured after a short time.

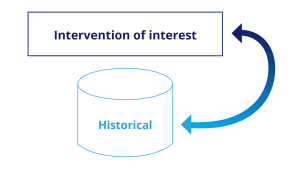

Historical Controls: Chronic Disease

In this design, prospective treated patients are compared to a control group taken from historical data, e.g., collected in a registry. This design is most appropriate when randomization is unethical or not possible. We recommend paying particular attention to the comparability of the groups, not only with respect to demographic and disease data, but also to the evaluation method used for the endpoint.

Adaptive Designs: Progressive Disease

Adaptive designs may minimize the total development time and reduce the number of patients required in a trial (see figure below). Sample size can be adapted to effect size at an interim stage, which can also include a stop for futility. One or more interim analyses may be included.

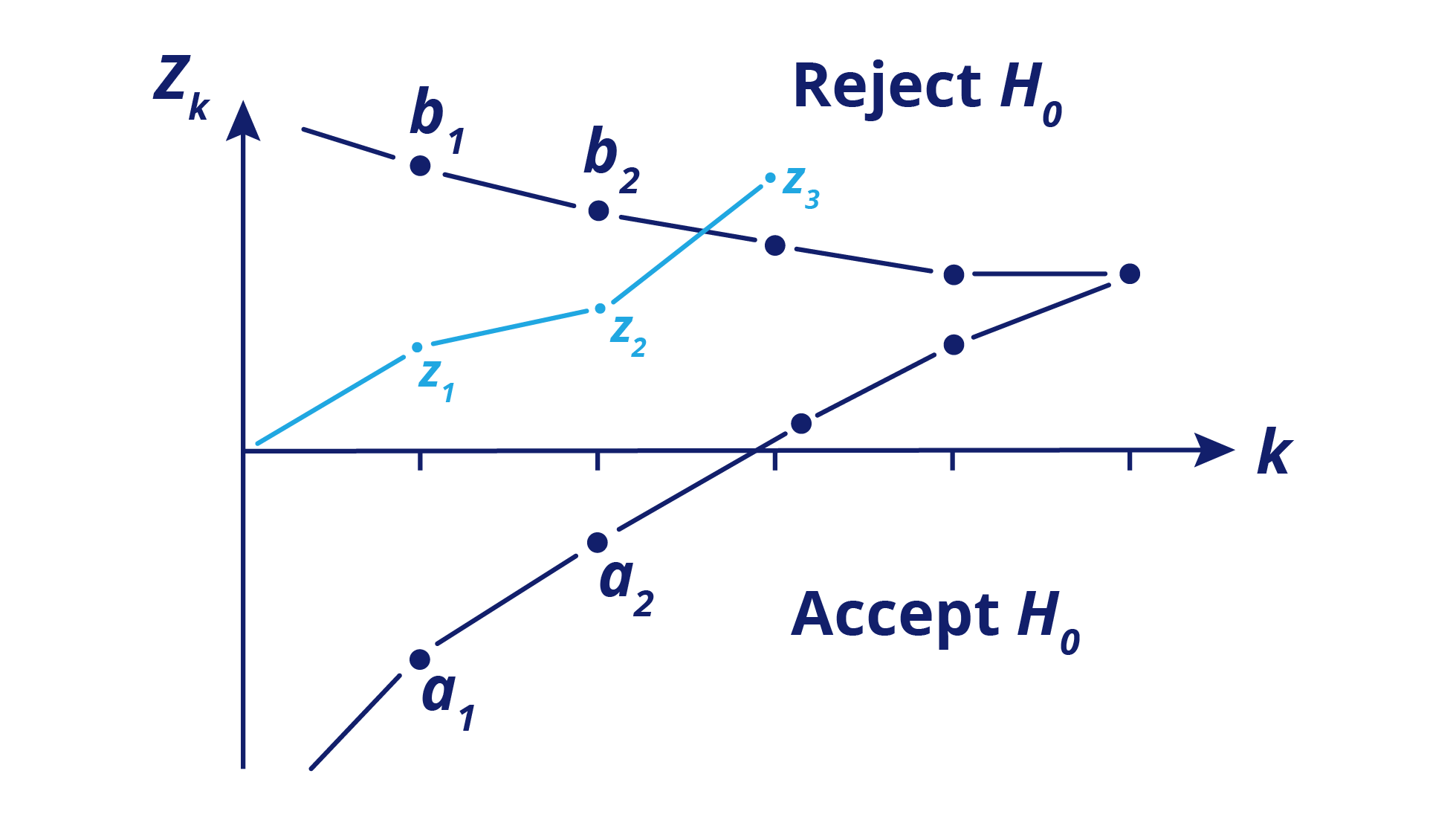

Sequential Designs: Progressive Disease

Sequential designs, either group sequential or full sequential, are most appropriate if a sponsor expects a large difference between treatments because they allow stopping for futility or success very early. It’s important to consider that this design has a logistical burden compared to others.

Additional recommendations

The Small Population Clinical Trials Task Force (IRDiRC) provides additional recommendations to minimize the number of patients to be included in a trial:

- Collect natural history and patient registry data for rare diseases for the design of clinical trials

- Trials should be long enough for complete follow up and patients should stay in trials for as long as possible

- Do not dichotomize continuous endpoints

- Use composite endpoints by combining several outcomes into a single outcome measure, thereby increasing the number of events

- Use analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) instead of simple “change from baseline” analyses

- Make full use of longitudinal data: Analysis methods for repeated measurements lead to a potential reduction of sample size by 30% versus change score analysis

References

- EMA/CHMP: Guideline on clinical trials in small populations. Retrieved from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-clinical-trials-smallpopulations_en.pdf(2006).

- FDA: Rare Diseases – Common Issues in Drug Development – Draft Guidance for Industry. Retrieved from: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm458485.pdf (2019)

- Kravitz RL, Duan N, eds, and the DEcIDE Methods Center N-of-1 Guidance Panel (Duan N, Eslick I, Gabler NB, Kaplan HC, Kravitz RL, Larson EB, Pace WD, Schmid CH, Sim I, Vohra S). Design and Implementation of N-of-1 Trials: A User’s Guide. AHRQ Publication No. 13(14)-EHC122-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; February 2014. Retrieved from: ahrq.gov/N-1-Trials.cfm.

- Neuenschwander B, Capkun-Niggli G, Branson M, Spiegelhalter DJ. Summarizing historical information on controls in clinical trials. Clinical Trials. 2010 Feb;7(1):5-18

- Design of randomized controlled confirmatory trials using historical control data to augment sample size for concurrent controls. Yuan J, Liu J, Zhu R, Lu Y, Palm U. J; Biopharm Stat. 2019;29(3):558-573.

- Lim J, Walley R, Yuan J, Liu J, Dabral A, Best N, Grieve A, Hampson L, Wolfram J, Woodward P, Yong F, Zhang X, Bowen E. Minimizing Patient Burden Through the Use of Historical Subject-Level Data in Innovative Confirmatory Clinical Trials: Review of Methods and Opportunities. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2018 Sep;52(5):546-559.

- Deepak L. Bhatt, M.D., M.P.H., and Cyrus Mehta, Ph.D.: Adaptive Designs for Clinical Trials N Engl J Med 2016;375:65-74.

- Cyrus Mehta, Ph.D.; Ping Gao, Ph.D.; Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH; Robert A. Harrington, MD; Simona Skerjanec, PharmD; James H. Ware, Ph.D.: Optimizing Trial Design – Sequential, Adaptive, and Enrichment Strategies. Circulation. 2009;119:597-605. Retrieved from: http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/119/4/597

- Day, S., Jonker, A.H., Lau, L.P.L. et al. Recommendations for the design of small population clinical trials. Orphanet J Rare Dis 13, 195 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-018-0931-2

Subscribe to our newsletter for the latest news, events, and thought leadership